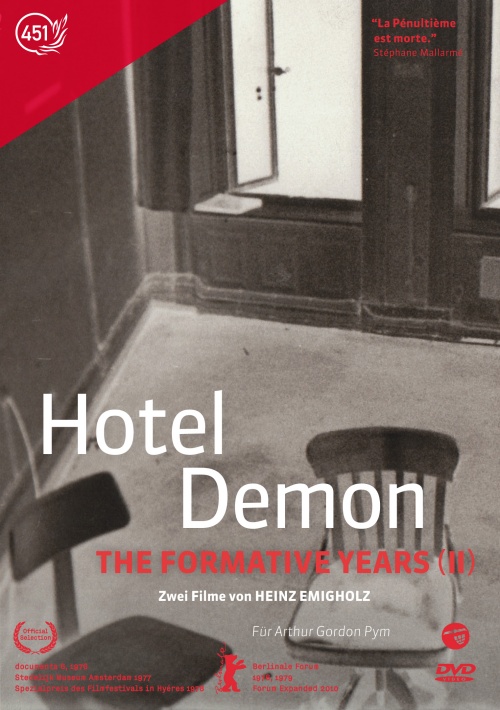

The formative Years (II)

GER 1975-77, 56 min

The project THE FORMATIVE YEARS makes visible and accessible seven early experimental works by Heinz Emigholz, which provided a crucial impetus for the international experimental film movement of the 1970s and 80s. They are counted among the few experimental works from Germany which have attained enduring international acclaim.

In HOTEL Heinz Emigholz ruptures temporally linear shots by breaking them apart and then editing these parts into one another according to recognizable patterns. While in DEMON Emigholz has given a spatial element to the words and thus approached Mallarmé's dream to be able to show that language can be an object, a counterpart.

Synopsis

HOTEL

(GER 1975/76, 27 min, b/w, silent and original sound)

The title of the film is an hommage to Jack Smith's shows, such as ‚Lucky Landlordism of Rented Paradise‘ for example, especially however to ‚Horrror of the Rented World‘, his stage performance at Collective for Living Cinema in 1975. The wise insight of those times was the phrase – its proclamation all over the world osciallting between unruly and tender: “I am a tourist here myself.”

DEMON

(GER 1976/77, 29 min, b/w and color, original sound)

The Translation of Stéphane Mallarmé´s “The Demon of Analogy”.

Press reviews

HOTEL is one of the clearest, and at the same time most beautiful films, that has ever been made about time in film. In several episodes, Emigholz ruptures temporally linear shots by breaking them apart and then editing these parts into one another according to recognizable patterns. (Peter Tscherkassky)

HOTEL is in three sections. In the first, a hand-held camera follows two men walking on a desolate urban street. During the filming, the filmmaker tracked behind the men, walking at their pace, filming in slow motion, and making extremely rapid, small reframing jiggles, with the camera. We see the men walking very slowly; we have a sense that the camera is also moving forward in slow motion, yet the reframing movements appear to be at normal speed. This disjunction between the speed of the tracking and the speed of the reframing is disorienting. The street takes on an anxious science-fiction quality. (Amy Taubin, THE SOHO WEEKLY NEWS, 01.02.1979)

Additional Texts

On DEMON

(Marcia Bronstein)

Objects

The cups and the saucers on the breakfast table bulge out at us, every day, in perfect, smirking symmetry, rule our field of vision in a way unaccounted for by the bare functions they fulfill. Out the window, slung over a chair, are forms so barbed, so crazy, calling out in a continuous, untranslatable appeal.

What Emigholz does in his work is begin to isolate, to catalogue, these things co-existing with us, to take them from the context in which they dwell, cleverly disguised as the rudiments of bland existence, and display them as the strange foreign bodies they are. Objects in Emigholz’ work include those things we simply handle every day, but he also deals with less tangible things - quality of illumination as object; words, platitudes, internalized admonitions as object; sense or the conventional structuring of sense as object. He makes associations among these things, drawing analogies that are cleanly tuned, but in the end he draws no tidy conclusions. Objects in his work are put to use as metaphor, strung into patterns of sense, but they also, very importantly, retain their essential unknowability, their hard, impassive, ungiving side, refusing to be completely interpreted or categorized, refusing to have eyes, nose, and smile drawn on them and wiggle around for our amusement. These things that we reach over in the morning, en route to the salt, or pass on our way to work, or flip through and read are not cute or harmless, they are potent, caustic; in some strange way, like nothing we will ever be able to fully understand, they command. Watching one of Emigholz’s films is like moving around, in reality, with a constant awareness, a sixth sense, for the sharp corners everywhere, for the edge, the charge, hidden in every thing.

Separation

DEMON, subtitled „The Translation of Stéphane Mallarmé’s THE DEMON OF ANALOGY“, includes the Mallarmé text, spoken by various performers in its original French version, and in English and German as well.

Most of the shots in the film are one word long. In the first scene, three women sit on chairs placed in the foreground of a room and a corps of men stands behind them, spread out over the rest of the space. The woman who is seated in the middle of the three speaks the first word of the Mallarmé text in her particular language with the men arranged behind her; there is a cut, another woman sits in the middle, speaking the first word of the text in her, different language with the men in a new arrangement behind her, cut, another in her language, then back to the first for the next word of the text. From this point on although the poem progresses forward in all three languages the order of shots – French word, English word, German word, doesn’t remain fixed.

Single words take little time to say, and the pacing of these shots is rapid, relentless, even more so since there is never a continuous linear cut between shots. The effect is strong, assaulting, as if a crystal mounted on a motor were throwing off fast stab after stab of light.

Halfway through the continuing recitation the action moves off to a new location where a new group of women recites in the foreground and a full-to-bursting tool shop window behind them stands in for the men. Punctuating the film throughout are wordless and unpeopled stretches, some of them almost invisible in their brown, lapping benignity, and put it, I’ve always assumed, when the text itself called for an intake of breath.

The Mallarmé piece you are free to follow from beginning to end in the language you best understand - it’s all there. But the words of the text have been separated from each other to the extent that they easily snap off from the body of the poem and go out on their own to activate numerous, refined, sly associations with what there is to see. In fact comprehension of the text is the first facile use of it sacrificed in this particular rendition. On its own an emotional piece, masquerading as a soliloquy on language and the generating of it, and the invoking power of words, the text has not been illustrated or clarified here, but supplanted by something completely different, which causes you to reflect back on words from the vantage point of Emigholz’s concerns and which brings his emotions into play.

Mallarmé´s text is a mock obituary. He mourns „The penult“ (the next to the last syllable in a word, the next to the last step in a process, as well) which, as he insists again and again till he convinces himself, „is dead“. The extent to which he becomes worked up over it causes the piece to emerge from its linguistic context and move into the realm where real mechanisms of separation and loss become enacted. The effect is almost moving. The text is as wry as it is difficult, protesting, distracted. Some real loss (or discovery), it is felt, is given shape, but since the piece describes no more than a staged linguistic event, it is, rather than a lamentation over the loss of these parts of words, a celebration of their existence.

When Emigholz dismantles the text, which is practically asking for it, the words do become celebrated in their own right. The pictures he sets them against bring his own concerns to the fore. Consider the male performers in the sequence (the „ballet“) described above, slumbing and jump-cutting around mutely and obediently from one wall to the other, and the display of women up front, sitting and speaking. This is another version of the truce, let’s call it, uneasy and unfulfilling as it might be, between women and men that Emigholz in his drawings has often pictured. As usual the women are given more than a decorative function. Yet that their apparent control is being parodied is very clear in how puppet-like all the performers are made to behave.

You could read the phone book to such a scene and it would still have some force. But to hear Mallarmé’s rambling plaint about the murder of the penult, the whole thing full of his growing conviction of being left in the lurch, adds the individual’s query about where he´s supposed to belong, to this picture of role separation. It’s funny as well as pained. The rest of the film as well prickles with sharp sentiments.

Disjunction

The particular kind of disjunction that Emigholz effects in his work comes about in trying to represent a space, or a shape, through film, greater in its dimensions than film’s linear format allows. In trying to show various sides of a thing at once, like a poem in three simultaneous versions, you end up with a schematicization of this shape, like a 3-D projection constructed co-ordinate after co-ordinate, that is shot after shot. Hovering over many of Emigholz’s films is that ghost of a 3-D shape, complex and beautiful, that the film itself is wishing towards. What he did with one poem, the synonyms in three different languages moving further and further away from one another as the translations diverge, he does with one landscape panorama in other films. To grasp more than the presence, the shadow of this thing is not the point. The skewed associations that you are guided to make instead as the film burgeons out of your grasp – the errors in perception, for example, which of course are only human, which is what makes them so interesting to observe – become the point. These are not films about film, but films about brainwork. DEMON is about that part of brainwork known broadly as language comprehension, and in particular about the chemistry of words. Incidentally, the more languages you know the more there is to witness in yourself coming to terms with the words you are given.

Credits

HOTEL

Director, Concept, Director of Photography, Editor and Producer

Heinz Emigholz

With

Silke Grossmann, Heinz Emigholz

Sound

Marcia Bronstein

German Premiere

documenta 6, 26.08.1976

DEMON

Director, Concept, Director of Photography, Editor and Producer

Heinz Emigholz

With

Marcia Bronstein, Susanne Christmann, Silke Grossmann, Hilka Nordhausen, Gabriele Kreis, Renée Pötzscher, Christoph Derschau, Bodo von Dewitz, Hannes Hatje, Gernot Meyer, Steffen Poppenberg, Klaus Wyborny

Sound

Marcia Bronstein

World Premiere

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 22.09.1977

German Premiere

Berlinale Forum, 1979

DVD-Details

HOTEL and DEMON were published on the DVD THE FORMATIVE YEARS (II)

Extras

Interview with Heinz Emigholz and Klaus Wyborny (96 min, german with english subtitles), Sound slide shows (SCHUHSTÜCK - 1976, b/w, 8 min, sound + TASSENSTÜCK - 1976, b/w, 3 min, sound + WANDSBEK GARTENSTÜCK - 1976, Color, 15 min, sound), 20 pages booklet

Language

International Version (no dialogues)

Length

56 min + 120 min Extras

Aspect Ratio

4:3

Sound Format

DD 2.0

Country Code

Code-free

System

NTSC / Color + b/w

Content

Softbox (Set Content: 1), 20-pages Booklet

Release

05.02.2010

Rating

Info-Programm gemäß §14 JuSchG

Distribution Details

Screening Format

ProRes File

16 mm

Aspect Ratio

16 mm, 1:1,38

Language

HOTEL: international version (no dialogue)

DEMON: French, English, German

Promotion Material

A1 Poster

License Area

Worldwide

Rating

Info-Programm gemäß §14 JuSchG