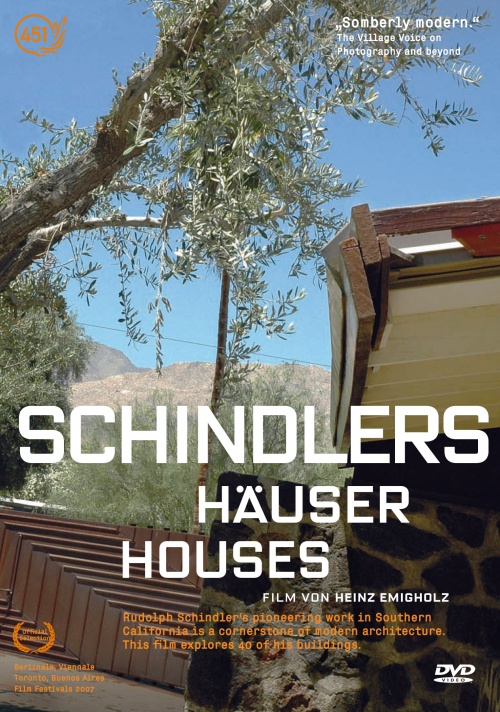

Schindler’s Houses

A 2007, 99 min

40 buildings by the Austro-American architect Rudolph Schindler from the years 1931 to 1952. Schindler’s pioneering work in Southern California is the cornerstone of a branch of modern architecture.

Synopsis

The Austrian-American architect Rudolph Schindler (1887-1953) worked with Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright at the beginning of his career. Like Bruce Goff, he is a singularity of modernism and the founder of his own Californian style of building. His turn away from the “International Style” isolated him in the world of architecture for many years. His style is characterized by the use of wood and by the unified design of furnishings for entire households. His own home, built in 1922 in West Hollywood, is considered an epochal masterpiece.

SCHINDLER’S HOUSES documents the interiors and exteriors of 40 of his houses in and around Los Angeles in the context of their surroundings today. Using no voiceover, archival photos, or other conventions of standard documentaries, the film presents beautifully composed shots of the 40 buildings in the order in which they were built. Emigholz’s style is formal and subtle, but the cumulative effect is a provocative meditation on Schindler’s ideas regarding architecture and environment.

Streaming-Info

Rent or buy the movie on Vimeo.

Language: English

Film kaufen

VOD

451-Vimeo

DVD

451-Alive Shop

amazon

Press reviews

Packed houses at the Heinz Emigholz’s marvelously spare documentary SCHINDLER’S HOUSES, in which a series of static images of forty homes designed by modernist architect Rudolph Schindler had the cumulative effect of becoming one of the most compelling textural portraits of urban Los Angeles ever filmed. (indieWIRE)

Awards and Festivals

- Berlinale Forum, 2007

- Mar Del Plata Film Festival, 2007

- Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Film, 2007

- Toronto Filmfestival, 2007

- Vancouver Filmfestival, 2007

- Viennale – Vienna International Film Festival, 2007

- New Horizons IFF, 2007

- Diagonale – Festival des österreichischen Films, 2009

Additional Texts

Rudolph M. Schindler

Rudolph M. Schindler (1887-1953) was born in Vienna, where he studied under architects Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos. Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1910 Wasmuth portfolio, he came to Chicago in 1914 and began to work for Wright in 1918. Wright sent him to Los Angeles in 1920 to supervise the construction of the Hollyhock House for Aline Barnsdall. Schindler established his practice there in 1922 with his own Kings Road House, a house designed as live-work space for two couples with a shared kitchen and an apartment for guests. Schindlers work focused on the integration of interior space and exterior space using complex interlocking volumes and strongly articulated sections. He designed over 400 projects, 150 of which were built during his career. These consisted largely of lowcost single family houses for progressive clients. Although the materials and vocabulary of Schindlers work changed during the span of his career, his principles of design and spatial characteristics were consistent throughout his work. This is true even as his spatial ideas evolved in his late work, including the translucent houses of the mid-1940s to early-1950s.

Kathryn Smith, architecture historian and author of “Schindler House” (MAK Center for Art and Architecture / The Schindler House, LA)

On SCHINDLER’S HOUSES

by Mary Ries

Heinz Emigholz makes portraits of houses that can be ascribed to one architect, Rudolph M. Schindler. With that Schindler as a person becomes part of the house portraits though what we learn through the filmic description is, however, is something different and more. The portraits of the 40 houses allow one to discern their form, the construction of their interiors, their life together with their surroundings and society, the way they can be used and, therefore, the marks left by their lives of those inhabiting them and their history. The excitement deriving from the fascination with Schindler’s buildings is combined with views of the idiom of everyday Californian life, with depictions of the obscene coupling of plants and houses and with the force of an “authorship related to society as a whole” (Emigholz), with what is called architecture.

But what possibilities does the film have to produce a portrait that is understood in this way? It is apparent that success can only come to pass when questions of space become questions of image, when questions of building and living become questions about the filmic gaze. I would like to try and reconstruct these movements. The take is, technically, the smallest unit of the film. For Emigholz however, it is simultaneously the centre of the power of a location in space.

This one place – in its immobility, in its constant view of the architecture – allows all the elements from within the chosen framing to flow into it and compressed in it is the resonance of the building, the greenery, life. The gaze has the leisure of al- lowing this to take effect, it is able to let the mind move around in the frame. The intentional intransigence of the camera position evokes mental movement. Viewers are able to use their imagination to put themselves into the room in place of the camera and, therefore, to appropriate and transform living in this place. This undertaking is assisted by the slight vertical tilt to the frame offering the gaze a “lopsided” way into the picture since filmic illusionism too can only be overturned like this. Perhaps the sound also has an essential part in this movement because it is through it that “a lot that cannot be seen in the picture is brought into it” (Emigholz); the vibrations of urban exist- ence, everyday melodies, the sounds of activity.

The acoustics which are simultaneously concen- trated and diffuse programme a kind of subversive animation of the buildings that are themselves lo- cated in quiet places. In this evocation of single camera positions it is possible to discern a position attributable to a pragmatic aesthetic: that an im- age opens up proportional to the desire behind the gaze to visualise the experience of this other house, this other city, this other country, to comprehend it and perhaps to add it to one‘s own image of living.

But then there is another take and then another and yet another. These work together to pull the architecture out of its – unintentional – hideaway into a genuine filmic space. The composition of the takes make changes of viewpoint, examination and insights possible that the occupants them- selves would probably miss. The hideaway here, in the case of SCHINDLERS HÄUSER [SCHINDLER‘S HOUSES], is always a double one. In the first place the architecture is hidden behind the vegetation, the enclosed space, the everyday signs. In the second place hiding is an inherently filmic proc- ess. One of these takes follows the logic of the hors-champs, that is, the simultaneous showing and not showing. The concealment of reality through the process of framing – what André Bazin called the operation of the cache – is, however, with the addition of a further point of view and yet another during the editing process, slightly eroded, the hidden is revealed – but not completely. That too, is impossible, there is always a remainer of what is unseen, a secret which is necessarily kept. One of the insights of this film is not to pretend that one is in the position of showing everything, the “whole” architecture, but rather to let the whole, with its with all its “shadings”, reveal itself in only a few takes. When a portrait like this is finished – its duration certainly dependent on the relationship of house and author – in many respects one really does have the impression of having encountered the house and when one has seen all the portraits many of the questions about style, inhabitability, about the relationship between organic growth and structural alterations and ephemerality, about the meta-forming of buildings by society... a possible answer. The works its way from one portrait to the next and is thus, in sum total, a kind of al- bum, a filmic whiteboard onto which a multiply-occupied white/pure modern architecture is projected with the white/pure light of the cinema.

Interview with Heinz Emigholz on SCHINDLER’S HOUSES

Marc Ries: What was your first encounter with Schindler like?

Heinz Emigholz: In 1975, I happened to pass the Lovell House in Newport Beach. At first sight, the building struck me as simultaneously strange and well-conceived. But at that time, as a filmmaker I was working on extremely time-analytical compositions with no though of architecture outside the medium of time. Only later did my film work expand to issues and depictions of space. And I had forgotten my encounter with the house until I saw it again on a shooting trip in May 2006. Not until the end of the 1980s did I consciously notice a house or two by him in Los Angeles. A few years later, I developed the plan for the film series Photography and beyond. After Louis Sullivan and Robert Maillart, Schindler, together with Adolf Loos, Bruce Goff, and Freder- ick Kiesler, was the missing link to the present – at least as far as my feeling for space is concerned. The International Style and its expressionistic High-Tech sections never interested me.

How do you prepare for a shooting like this one – from the catalog to field research?

I don’t work on commission, so I am independent and can pursue what interests me. The decision to “encyclopedically” explore the work of a specific architect always began with a concrete experience of space. At least one room he built has to trigger an intense fondness in me; otherwise I can’t do any research. A certain kinship in spirit in regard to grasping, designing, and experiencing space is the starting point. From there, I research and extrapolate until I decide to open myself to the work of a specific person. Then we seek contacts and try to find allies for the project and to raise production money. In the end we plan a travel route that covers the accessible constructions. It all takes years.

Does your first on-site visit suffice to find “the” image?

I believe in first impressions and the analytical power of the first encounter. You never get a second chance to make a first impression. It just depends on how concentratedly you work. And with me, shootings are the time when my brain is 100 percent present in the real world. And the point isn’t “the” image – some single, representative image – but a cinematic context, a sequence of individual images that the editing and the viewer’s memory turn into a spatial situation.

Can it be that the Schindler houses display a kind of inner montage that meets the films halfway? The interior space is not divided into separate units, but is usually a larger, convoluted room that presents a wide range of perspectives and thus accommodates the cinematic way of seeing in montage.

It so happened that last spring, around the time of the Schindler shooting, I filmed almost all still-existing constructions by Adolf Loos. The film is titled Loos ornamental and will be finished soon. Of course, the idea of his “spatial plan” is also evident in Schindler. The floor plan no longer plays a big role. What counts is the sphere in which our head moves freely in the space. Planned was a complex spatiality that interlocks on various levels and that really can’t be conceived and carried out except on site. That presupposes an extreme culture of craftsmanship, on which Loos, Schindler, and Goff could still count in their lifetimes. Incidentally, Loos’ Müller villa in Prague, which is the most elaborated project in this regard, is on a steep slope – like most of Schindler’s houses, as well. Views and perspectives of and from the house are built on the foundation of a complex natural situation. This is the opposite of formula architecture. The two films show how Schindler could carry out and further develop in freedom what Loos had conceived so consistently and the degree to which Loos had to land in a dead end here in Europe. Of course, with both I’m fascinated by the complex spatial situations, which open up countless perspectives. I work in this same direction as a cameraman – away from the falsely postulated clarity of space.

Was it difficult to film all the houses you found? Do you gain access everywhere?

There are good reasons not to let film teams into your home. Especially in Hollywood, where everyone knows that film teams destroy every place they enter. Or the residents are ill or on a long trip. Or a star doesn’t want people to know where he lives; a punk band doesn’t want it known how luxuriously it lives. And for many people in show biz, social contacts carry the risk that one might end up with the “wrong”, rather than the “right” people. House-hopping and upscale mobility on the real estate market are primary activities there. I respect that. A home is something very private. When we filmed, there were only three of us, and May Rigler spent months in Los Angeles building relationships of trust with the people living in the houses. Where we shot, we were received with a warmth that is probably possible only in America. But with Schindler, I reached a limit in an area that I don’t want to expose myself to anymore: in connection with shooting permissions and the idiosyncrasies of those who decide whether you can film or not. The reaction of certain architecture theorists was interesting. They acted as if our filming and documenting the houses was stealing their life theme. Faculty wars in the real, 3-D world – it was really funny. The deplorable custom in these circles of trying to make “representative” views mandatory had not, however, spread to the residents we got to know. Almost all the original owners were part of the artistic or scientific bohemia of Los Angeles. They wanted affordable, but still highly individualistically designed houses. Fortunately, that made these houses – though they are meanwhile legendary – too small to be interesting for a certain exclusive clientele. John Lautner is there for them. And fortunately, I have meanwhile filmed almost everything I ever wanted to of the so-called famous architects. And no one yet pays any attention to the anonymous architectonic sites that don’t have any name and that now interest me much more.

Today we have two ways to receive “auteur architecture”. First, via high-quality depictions in catalogs, in which objects are dissected from their contexts and celebrated as unique items. The other way is by encountering them on-site, which is in part promoted by an excessive architecture tourism. But between the two modes of reception a gap in experience often opens up that may imply an aesthetic gap, as well: the model in the catalog is “overshadowed” by its lived existence in an environment and in a history that leaves traces on the architecture, bringing something else out of it, maybe what you describe as the “originality of an authorship of the whole society”.

The aporias of architectural photography are well known. Limited space in the publication media leads to intensely staged condensa- tions and limitations to the supposedly essential – and to much use of wide-angle lenses, so that everything is captured in one picture. A human scale is thereby often lost. What is good for the architect’s sales brochures need not have anything to do with what one can experience in or through these rooms. I find architecture tourism interesting because one’s own physical experience of a constructed room relativizes its media representation, even casting it into doubt and opening it to criticism. The prologue of my film proclaims the crime that I then commit: the relative isolation of an auteur architecture from the context of a whole society. Many films about architecture try to quote this context into being by providing essayistic commentary. For me, that’s the wrong path, because it avoids the basic experience with an object. It would be much better to depict this context itself, as in the first take of SCHINDLER’S HOUSES. Incidentally, some of those who have seen the film say they constantly had the feeling of moving in a story or in rudiments of tales. And indeed, certain landscapes of the city of Los Angeles extend into the images, and many of the houses the film shows are seen in films shot in Los Angeles. But what is evident in SCHINDLER’S HOUSES is more the Los Angeles of Maya Deren, Thom Andersen, and David Lynch than that of Alan Rudolph and Wes Anderson.

Is the “aesthetic gap” a constituting one, perhaps an a priori component of your architecture-film work, or is it the result of what happens on site? It seems to me as if the milieu were less intensely present in Sullivan’s Banks than in the other works.

The gap you describe is more fundamental to film than to photography. The sound alone brings much into the film that is not in the picture. And film images are constantly “turned around” and set in new relationships in the sequence of takes. Attributions of significance logically cannot be as clear-cut in film as they can in photography, even if the director wanted to try. But I don’t have the aim of isolating and presenting ideal states. In these films, I don’t use historical footage, because I’m interested in the current existence of the buildings shown; that is, at a very specific time. I thereby also document the respective present day. That was already the case with Sullivan’s Banks.

The proliferation of green, of nature, is actually also a “subject” of the film. I had the impression that SCHINDLER’S HOUSES is also a film about nature reconquering civilization – through a strange affiliation of culture and na- ture that the houses have.

But that is no opposition. Schindler had very realistic visions of the effect the houses

would have in an environment that would not grow back until later. With many houses, the landscape around them was part of the plan. So he was also a landscape architect. He built in extreme places, in the wild, almost inaccessible mountain landscape that separates the Los Angeles Basin from the San Fernando Valley. Nature and its extreme conditions were always immediately a theme of his work. Many “results” of his work he never experienced, because nature did not play its part until decades after construction was completed. For example the Elliot House in Los Feliz: in the photos shortly after its completion in 1930, it stands visible from afar, like an abstract sculpture on a barren hill. Today it disappears in a bamboo forest, and only parts of the garage are still visible from the street. But in its structures, the house takes up the forms of the bamboo forest – which didn’t even exist at the time of construction. The Kings Road House, which was once way out in the sticks and now, unfortunately, is surrounded by blocklike apartment buildings, was concieved from th start as part of a large garden area. Schindler was downright obsessed with nature. He designed “sleeping porches” for his houses, where one could sleep outside. Nature was part of his thing.

How would you describe the state of (im)balance between the two levels of experien- ce that is important to you: here the object, there history and society?

From the level of the viewer. We are damned to view only surfaces. Most media surfaces unfortunately try to copy the acrobatics of words and to take part in their supposed authority. But it is part of the logic of the threedimensional world that the greatest number of images or pictorial contexts possible in it have never been shown or arisen in consciousness. At any rate, I am aware of a class of images that are yet to be made and that show the society and its respective “nature” without clinging to words.

Watch Movie

VOD

451-Vimeo

DVD

451-Alive Shop

amazon

Credits

Concept, Director, Director of Photography and Editor

Heinz Emigholz

Camera Assistant

Volkmar Geiblinger

Assistant Editor

Markus Ruff

Narrator

Christian Reiner

Original Sound

May Rigler

Sound Design

Jochen Jezussek, Christian Obermaier

Sound Mixer

Eckard Goebel

Production Coordination USA

May Rigler

Production Management

Alexander Glehr

Producer

Gabriele Kranzelbinder, Alexander Dumreicher-Ivanceanu

Produced by

Amour Fou

In Coproduction with

ORF Film-/Fernsehabkommen (Johanna Hanslmayr), WDR III (Jutta Krug) und WDR/3sat (Reinhard Wulf)

In Cooperation with

Heinz Emigholz Filmproduktion

With the Help of

Filmfonds Wien and Innovative Film Austria

DVD-Details

Extras

Additional shots, Biographies of Schindler and Emigholz, Building by building navigation, 16-pages Booklet

Language

German, English

Aspect Ratio

4:3

Sound Format

DD 5.1

Country Code

Code-free

System

NTSC / Color

Length

99 min + 40 min Extras

Content

Softbox (Set Content: 1), 16-pages Booklet

Release

14.09.2007

Rating

No age restriction

Distribution Details

Screening Format

35mm

Aspect Ratio

35mm: 1:1, 37

Language

International Version (no dialog)

Promotion Material

A1-Poster, Folder

License Area

Worldwide except Austria: Amour Fou

Rating

No age restriction