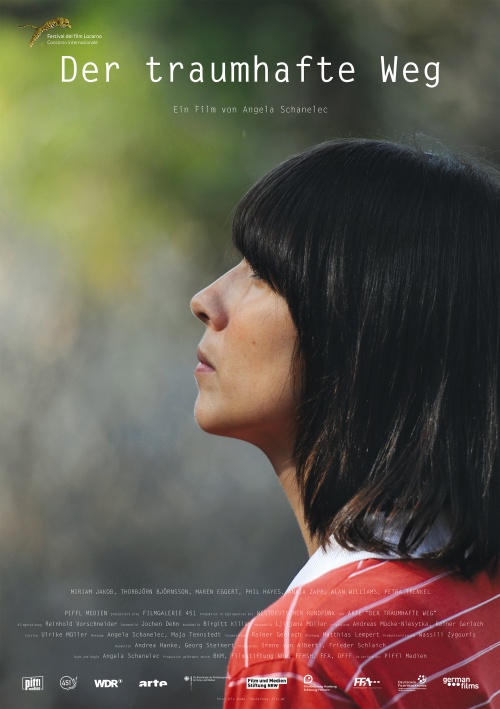

The dreamed Path

GER 2016, 86 min

Two couples suffer the failure of their relationships 30 years apart.

Synopsis

Greece, 1984. Kenneth, an Englishman, and Theres, a German girl, sing in the street to finance their holidays. They are in love, but when Kenneth learns that his mother had an accident, he hastily returns home, leaving Theres behind. Later, starting to realize how much he needs her, he fails in his attempt to win her back.

30 years later in Berlin. Ariane, a 40-year-old TV actress, leaves her husband, a successful anthropologist, after a marital crisis. After moving into an apartment near the main station, the husband starts seeing a homeless man outside his window. It is Kenneth, who does not know that Theres now also lives in Berlin.

Streaming-Info

Rent or buy the movie on our Vimeo channel. For other providers, see “Watch Movie”.

Language: German, English, Subtitles: English, French, German

Film kaufen

VOD

451-Vimeo

amazon

iTunes

Google Play

DVD

amazon

Press reviews

Angela Schanelec’s continued lack of recognition, at least outside of Germany, is genuinely baffling. Judging from the dismissive-to-hostile reactions that followed the premiere of her eighth feature at the Locarno Film Festival, this regrettable state of affairs is unlikely to change. And yet, out of the competition entries I managed to see, The Dreamed Path is the only one I feel deserves to be called a masterpiece.

he Dreamed Path is a demanding film, even more so than Schanelec’s previous work, but the challenge is legitimated by being commensurate with her thematic ambition: to dissect the torturous dialectic between the universal human need for connection and the invisible forces that inhibit its fulfillment. The narrative, which begins in the 1980s before shifting to the present about halfway through, is split between two couples, one young and one middle-aged. Schanelec deliberately keeps the particulars of the relationships and their ill-fated trajectories familiar and largely unexceptional in order to zero in on the underlying existential dimension. This strategy is elaborated through her choice of a 4:3 frame and by having the actors, for the most part non-professionals, deliver all their lines with Bressonian impassivity. The film’s mise en scène is constructed with the utmost precision, each element in every frame evincing purposeful intention. As with fellow Bresson disciple Pedro Costa, Schanelec’s rigorously austere aesthetic has the effect that any departure – a music cue, an aberrant camera movement, a single tear bursting through a face’s stony façade – is amplified to earth-shattering proportions and the sparing deployment of such moments engenders an expression of empathy that is as vigorous as it is unembellished.

Schanelec’s detractors often accuse her films of stasis. A more fitting description, certainly for The Dreamed Path, would be that they’re preoccupied with permanence. Although the film makes big chronological and geographical jumps, these are not signaled immediately but take place within ellipses and only become apparent through subtle clues, usually anachronisms introduced sometime after the fact. Through this tactic, along with the ironic background incorporation of historical developments promising a closer union amongst societies – e.g. Greece’s entry into the European Union, or German reunification – Schanelec frames the isolation afflicting her characters as an essential and immutable characteristic of the human condition. In this regard, it’s appropriate that she should invite comparison to Kafka by at one point showing a character with a collection of his stories. Although she doesn’t share the great author’s overt absurdism, her film evokes an analogous sense of entrapment and ineluctability. The Dreamed Path is not a cheerful film, no, but like Kafka’s writing, Schanelec’s cinema is not one of defeat. If it were, surrender would be a choice both understandable and inevitable, whereas it is unambiguously presented as the ultimate tragedy. (filmmakers, Giovanni Marchini Camia)

Angela Schanelec’s eighth feature, Der traumhafte Weg (The Dreamed Path), is a glorious existential sucker punch. Plot-wise, this wonderfully strange, narratively elliptical work from the Berlin School filmmaker moves between two worlds: a young couple’s holiday fling in Greece in 1984 that melts, unidentified, into the lives of an older couple who are separating in Berlin, thirty years later. Shot with chilling formal rigour, Schanelec manages to express everything—heroin addiction, the death of a parent, extinct hopes, solitude—through an intense Bressonian framing of mostly hands, feet, and torsos. The film builds its own trance-like rhythm while cold shouldering on-screen drama. Dialogue is stilted, sparse, each figure wrapped into themselves, and other than a cathartic burst of Flume’s remix of “You and Me”, most of the film passes in silence, stasis. When a young girl breaks her arm we only see her carry the ladder to a window and then her body resting on the floor, as if sleeping. Magnified by these gaps, the gestures of Schanelec’s lonely, aching bodies resonate far longer than any words. (Annabel Brady-Brown, fourthreefilm.com)

Awards and Festivals

- Festival del film Locarno - Concorso Internazionale 2016

- Toronto International Film Festival - Wavelengths 2016

- Filmfest Hamburg 2016

- Vancouver International Film Festival 2016

- Seville European Film Festival 2016

- Festival Internacional de Cine de Mar del Plata 2016

- Human Rights Film Festival, Zagreb 2016

- Film Festival Cologne 2016

- Braunschweig International Filmfestival 2016

- HEIMSPIEL – Regensburger Filmfest 2016

- Around the World in 14 Films, Berlin 2016

- International Film Festival Rotterdam - Deep Focus 2017

- Northwest Film Center’s 40th Portland International Film Festival 2017

- FICUNAM | Festival Internacional de Cine UNAM, Mexiko 2017

- Festival Internacional de Cine en Guadalajara, Mexiko 2017

- Mezinárodní filmový festival Praha – FEBIOFEST 2017

- New Directors/New Films Festival, Film Society of Lincoln Center & MoMA NY 2017

- Hong Kong International Film Festival 2017

- Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival 2017

- Locarno in Los Angeles Film Festival, Acropolis Cinema LA 2017

- Tabakalera, San Sebastián, Spanien 2017

- Jeonju International Film Festival, South Korea 2017

- IndieLisboa International Film Festival 2017

- Cine Palacio de la Prensa Madrid 2017

- Singapore International Film Festival 2017

- Lima Independiente International Film Festival 2017

- Letní filmová škola Uherské Hradiště 2017

- Melbourne International Film Festival 2017

- Filmwoche Buenos Aires 2017

- Indie Festival Brazil 2017

- Kino Visions Marseille 2017

- Festival du Cinéma allemand in Paris 2017

- Deutschen Filmtage in Bukarest 2017

- Golden Age Cinema Sydney 2018

- NUMAX Santiago de Compostela 2018

- Athénée Français Cultural Center Tokyo 2018

- Demachiza Cinema Kyoto 2018

- Genesis Cinema London 2018

- Spectacle Brooklyn NY 2018

Additional Texts

Christoph Hochhäusler talks to Angela Schanelec about her film THE DREAMED PATH (2016)

Christoph Hochhäusler: In many of your films the settings themselves play a leading role – Places in Cities, Marseille, Orlyexplicitly name the locations in their titles. Your new film is titled The Dreamed Path. Is that programmatic?

Angela Schanelec: This time thescenesfunction is more to outline a path; they are stages, and that becomes more palpable due to the factthat there are so many stagesand that this path is narrated over a very long period of time.

Many films–particularly when they attempt to relate biographical accounts over an extended period of time –follow some manner of “central perspective”, where an important event is in the offing over the course of many scenes. You do not follow that logic. What holds your film together?

I think the people;and – more precisely, perhaps – theirbodies.

Howdo you createyour characters? Penningcharactersis one thing, but is it that they do not truly become “film” until a bodyhasbeen found?

I have a specific being that I envision. That really describes it better, because, to me, the term “being” inherently means something that is not contrived, something that more or less already exists. Like someone who stands in front of you about whomyou try to discern something.

This time youworked with lots of laypeople, people you found or however one wishes to describe them.

Yes, in any case they were performers who had not yet been in front of a cameraor who had never acted before.

Sois thatthen a search for a vision,or were they, let’s say, encounters with strangers?

Yes, the search for a vision, for an image. Like with the character Kenneth, for example; given the homeless people I encounter every day, it became clear to me that the image I had of him was not about authenticity, it was much more about abstraction. And then I saw Thorbjörn Björnsson, who is a singer and someone who goes on stage, and then Iknew... I knew that character existed, that embodiment of my vision.

So what were you able to tell your casting director Ulrike Müller?

For example, for Theres, one of the main female protagonists, I told her to look among dancers. And that’s how shefound Miriam Jakob. On the other hand, I wanted to cast Maren Eggert because I had had experiences shooting with her that gave me a certain image of her as a person... I think it has to do with fondness, with my fondness of the characters in my screenplays,and I sense when an actor makes it possible for me to feel that fondness. They are things that person can’t change: his or her body, voice, how he or she moves, facial contours that are independent of any momentary expression. This interest in the body, Ibelieve, has to do with the search for somethingunconscious. How can I show a person if I wish to make visible that unconscious quality, which, to me, manifests itself as something compulsory, necessary, inescapable? Thatexpresses itself in body movement of the body.

What I find interesting isthatthe notion that the face cannotexpress anything means it is about showing. And, at the same time, showing is always allegorical. For example, when I see close-ups of shoes in your film it is not an expression of interest in shoes...

The shoes convey a sense of the feet, which are walking or standing. If I want to relate that someone is standing or walking and only show feet, then the imagealludes to the person while also pointingbeyond that person.

That isactually a verbalization. And that is something new for you, isn’t it? The sequence shot, which is a very defining element of your other films, tends to be non-narrative, that is, it is a state that unfolds but that, to begin with, perhaps just is.

Yes,but it was also always about an inescapability, simply via the awareness of the passing of time, which I do not influence in that I don’t edit it.And this not influencing things emergesagain now; I can influence how the actors act,but I cannot influence their bodies. The shoes are expressionless, I cannot direct the shoes. Nowthe staging of the scene happens with the cuts and the sequencing of shots, and due to the excerpt-like quality of the film I was forced to shootconsiderably more takes. And, yes, that was new for me.

There is a very interesting paradox –or maybe it isn’t a paradox inyour mind–but, on the one hand, there is thedevelopment of alinguistic qualityand a joy in narrating, or an endeavour to narrate, yet, at the same time, there is a story that makes no effort to arriveata final tally and is full of enigmas.

It is another language, but what I want to tell... It is essentially just another way for me to deal with something that I cannot resolve, I cannot summarize it or clarify it. That’s not my topic.

You once saidbeauty is your topic, or your endeavour to attain it. Can you try to explain what beauty is?

I believe that, for me, beautyis solace. If I take things seriously,then the narrative develops without solace.And the definitiveness with which one thing follows another up untilthe end is something I am unable to escape. But,in order to not escape that end, I need a certain beauty of form; I can’t conceive of it any other way.

For instance, I really like the first shot, with the hair in the wind. Why does that console us? Of course, that is, in a sense, unanswerable.

If I weren’t able to findthings or people beautiful and to concludefor myself that there must be a reason for that beauty, then I wouldn’t feel the need to tell a story. For me, that beauty is bound to truth. It is something I believe in, something I think is true and that helps me along. It can be a gesture, a sentence... For example, when I first started thinking about the film I was reading Tristes Tropiques, which influenced me, my point of view and my perception. In any case, I came across a sentence from Claude Lévi Strauss that continued to occupy my mind: “... namely, understanding that man is a living being, and thus a suffering being, before he is a thinking being.” “And one can say I wanted to find a form for that.”

Toronto 2016 Review: THE DREAMED PATH, A Minimalist Masterwork

(Ben Umstead, Screenanarchy, 12.09.2016)

German director Angela Schanelec’s latest look at the nature of migration, stasis and loneliness should prove an equally striking and challenging cinematic event for new viewers, while previous enthusiasts of her opaque and minimalist oeuvre will be elated by this subtle masterstroke, one that is filled with powerful political nuance.

The above statement is a bold one to be sure, but as someone who has patiently waited six years since Schanelec’s last feature, the multi-narrative Orly, I feel very satisfied in saying as such.

It is important to note that while her near 20 year career has yielded multiple premieres at top tier festivals like Cannes and Locarno, unlike her contemporary Christian Petzold, Schanelec remains largely obscure outside of her native land. While The Dreamed Path is in no way enough of an accessible title to warrant wide exposure even on the indie circuit, the distribution landscape has changed enough since Orly’s premiere in 2010 to suggest that cinephile minded outlets like Fandor should be picking her Bressonian catalog up post haste.

Rich and profound in vision, The Dreamed Path flows with a beguiling ease, but is certainly not a lucid affair. Exposition is absent, with plotting a mere shadow. While the narrative is all there, you need to pay close attention. Details can often be found in the framing of silences more so than the glacial tone of dialog. The film works in two parts, each tale chronicling the deterioration of couples in their relationships, some 30 years apart. The first story begins in 1984, and follows young German Theres (Miriam Jakob) and Englishman Kenneth (Thorbjörn Björnsson) as they travel through Greece, eventually back to Germany, and when Kenneth finds out his mother is seriously ill, he moves on alone to the U.K.. Their separate threads continue through the decade, up until a few months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. The second story is set in present day Berlin and features Ariane (Maren Eggert), an actress, David (Phil Hayes), her often absent anthropologist husband, and their ten-year old daughter Fanny (Anaïa Zapp).

While both stories intersect tangentially, most connections between them are found in thematic motifs and aesthetic choices that find their rhythms across the film’s 86 minutes. Schanelec and her long-time cinematographer Reinhold Vorschneider’s brilliant form of minimalism is so stark that it distils and maximizes time and space to such an effect that the impact of the image we are left with is equally pure and abstracted; rife with meaning and desolation.

Take for instance the seemingly simple shot of water being poured from a pitcher to a glass. It is perfectly centered in the 4:3 frame. A late afternoon light cuts through, casting a crystallized shadow on the table. Instead of moving onto close ups of the conversation that is at the heart of this scene (one about belief in God and the frustration of his absence) Schanelec stays on the glass until it is emptied. Consider also the moment Kenneth calls home and gets the bad news about his mother. This takes places after he and Theres sit on the sidewalk busking for a few bucks, singing a sweet and tender little version of “The Lion Sleeps Tonight”. Instead of cutting to his reaction of the news, Schanelec stays on his shoes, the dropping of his cap, then moves to Theres’ reaction, then a torso only shot of a police man catching him before he falls. We then cut to a bunch of Greek youths in the back of a van, then a dog and woman, who asks what has happened. Schanelec very sparingly uses close ups of faces. The few that are used emotionally count for all the absent moments, months and years.

This expert focus on abstraction through realism is key to the film’s lasting power in a number of ways. A visual motif through both stories is the use of feet and hands, sometimes idle, at other times busy. Indeed the opening of the film consists of close ups of Theres and Kenneth's feet and hands as they scramble up a wooded hillside. Another repeating theme with bodies is illness and disability, from Kenneth’s mother’s comatose state, to his father’s (Alan Williams) near blindness, to Fanny breaking her arm, and a paraplegic boy she swims with at the pool. It is important to note that in a film full of intimate disconnection Kenneth’s father and Fanny may in fact be the most present and resilient characters. What we also find in these threads then is the further compression and acceleration of action through seeming stasis and altered ways of living. For nearly all major story points revolve around these conditions and happenings.

Like all of her work, from the coming-of-age journey Places in Cities to the arcane yet enveloping Marseille, Schanelc is very much interested in migration between modern and liminal borders. The suggested inter-play of Germany, the U.K. and Greece in the first story creates a striking thread of histories when one considers how each of these countries has affected European politics and trade in recent years. Indeed, if the film is about people’s inherent inability to connect than it is also about union and unity, not only between people, but between countries, and especially between one's faith and one’s own body and senses.

As such, The Dreamed Path is very much about the ways we watch each other and the world around us. While the emotions of its characters are held tightly to the periphery of the frame, it is in fact through the observational way we enter the work that we are able to relate to their feelings of emptiness. That is not to say the film is dour in conclusion. Very much like its title, The Dreamed Path suggests just as much hope as it does regret. And so, like many masterworks inspired by the likes of Bresson and Kieslowski, Schanelec’s film is cinema as question, and nothing more.

That question, of course, is multiple choice, etched by many paths, stretching out across generations, borders, class systems and beyond.

Watch Movie

VOD

451-Vimeo

amazon

iTunes

Google Play

DVD

amazon

Credits

Director and Screenplay

Angela Schanelec

With

Miriam Jakob, Thorbjörn Björnsson, Maren Eggert, Phil Hayes, Anaïa Zapp, Alan Williams, Miriam Horwitz, Benjamin Hassmann, Petra Trenkel, Michel Drobnik, Ben Carter, Caroline Garnell, Arthur Marioth, Leo Heim, Steffi Niederzoll, Esther Buss, Paula Knüpling, Helena Hentschel, Louis Schanelec, Nicolas Wackerbarth

Director of Photography

Reinhold Vorschneider

Original Sound

Andreas Mücke-Niesytka, Rainer Gerlach

Production Design

Jochen Dehn

Costume Design

Birgitt Kilian

Make-up Artist

Ljiljana Müller

Casting

Ulrike Müller

Script Counselling

Ludger Blanke

Editor

Angela Schanelec, Maja Tennstedt

Sound Design

Rainer Gerlach

Sound Supervisor and Sound Mixer

Matthias Lempert

Color Grading

Dirk Meier

Assistant Director

Kerstin Rexrodt, Stefan Nickel

Continuity

Frederic Moriette, Sunny Scheucher

Assistant Costume Design

Kerstin Feldmann

Costume's Trainee

Victoria Mehle

Assistant Production Design

Marie-Luise Balzer, Ann-Kristin Danzinger

Art Director

Pegah Ghalambor, Jan Hormann

Stand By Prop

Laura Nendza

Additional Make-up

Sandra Stockmeier, Julia Boehm, Lena Brendle

Key Grip

Sven Meyer, Armin Sieghaft

Lighting

Florian Heinrich, Sulev Rikko, Stefan Deuz, Tom Sperling, Valentin Huber, Halem Firat

1st AC

Holger Pest, Julian Taro Hitomi, Florian Geyer

2nd AC

Bilal Kuala, Milian Symanek, Ingo Blacha, Paul Günther

DIT

Maximilian Link

Dolly Grip

Ulrich Fassbender, Mario Matic, Nicolaus Metzger

Assistant Sound

Marco Krüger, Kai Lüde

Additional Editing

Halina Daugird

Still Photography

Iris Janke

Production Coordinator

Ola Czarniecka

Set Manager

Martin Mantel, Kevin Know

Set Manager Assistant

Florian Hohensee

Location Scouts

Philipp Karg, Rüdiger Jordan, Toby Ashraf, Christoph Otto, Nele Jeromin

Set Trainee

Paul von Heymann

Children's Caregiver

Konrad Schlaich

Assistant Producer

Julia Jacob, Viviana Kammel

Production Manager WDR

Oliver Wissmann

Production Coordinator

Mayra Magalhães

Production Accountant

Hans-Jürgen Bubser, Malek Jaserick

Service Production London

Tigerlily Films - Natasha Dack, Nikki Parrott

Service Production Athens

Homemade Films - Maria Drandaki

Postproduction Manager

Rebekka Garrido

Production Manager

Wassili Zygouris

Producer

Frieder Schlaich, Irene von Alberti

Produced by

Filmgalerie 451

Co-produced by

WDR (Andrea Hanke) und Arte (Georg Steinert)

Funded by

Beauftragter der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien, Film- und Medienstiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Filmförderung Hamburg Schleswig-Holstein, Filmförderungsanstalt und Deutscher Filmförderfonds

World Premiere

09.08.2016, Locarno, IFF

Distribution Details

German Distribution

Piffl Medien

International Distribution

Filmgalerie 451

(with exception of Germany, Austria, Brazil)

Screening Format

DCP (2K, 24 fps, 5.1)

Blu-ray Disc

Aspect Ratio

16:9

Language

German, English

Subtitles

English, French, German

Promotion Material

Trailer, A1 poster

License Area

Worldwide (with exception of Germany, Austria, Brazil)

Rating

From 12 years