Day of the Sparrow

GER 2010, 100 min

A political wildlife film that centres around a country where the border between war and peace fades.

Synopsis

On November 14, 2005, a sparrow is shot dead in Leeuwarden, and a German soldier dies in Kabul. With the headlines appearing side by side, Philip Scheffner is induced to use ornithological methods in his quest for the war. His journey through Germany begins at the Baltic Sea, with childhood memories at a bird sanctuary situated between a military training zone and a sailing marina.

From place to place, the camera circles the reality of war, in seemingly peaceful images. Conversations from coincidental meetings blow across the deserted landscape, birds staying in the focus of the lens at all times. They sit in cannon barrels, on fences, flutter across meadows and fields, marking the locations where the current war is contrived. And suddenly the perspective changes. A friend of the filmmaker is arrested on a village street in Brandenburg. The bird watchers themselves become the object of observation. The journey ends with a slightly displaced view of the familiar: a military training zone at the Baltic Sea situated between a bird sanctuary and a sailing marina. Missileimpacts lash the turquoise blue water; the birds above continue unswervingly onward.

Streaming-Info

Rent or buy the movie on our Vimeo channel.

Language: German, English, Subtitles: German

Awards and Festivals

- Klaus-Wildenhahn-Award of the Hamburg Documentary Week 2010

- City of Ludwigsburg Award at the German Documentary Awards 2011

Additional Texts

Statement of the Director

Since the age of eight, I have been watching birds with my binoculars. A hobby which has become an obsession in the meantime - as a teenager, I spent my vacations doing voluntary work in the Wallnau bird sanctuary on the island of Fehmarn and in Behrensdorf at the Hohwachter bay. A place where my family spent their vacations over several years and my father filmed our family and the sea with his Super-8 camera. The place itself, but especially its soundscape – comprising sounds of the sea, the chirping of birds and the sounds of antiaircraft missiles blasts – remain imprinted on my memory. Not as a threat, but rather as part of a promising “holiday soundtrack”. It was only my mother, who had experienced air raids during the Second World War, who retired on such days to the confines of the holiday cottage.

At the bird sanctuary, I met people doing their compulsory civil service who essentially shaped my stance on the military and the Bundeswehr. It was beyond all doubt that I would refuse to serve in the army. In the end, I was lucky and was exempted. In subsequent years, I increasingly swapped my binoculars for a microphone and camera. Nevertheless, I returned on a regular basis – also for filming – to the Baltic Sea.

There are some similarities in the work of a documentary filmmaker and a bird watcher. In both cases, the doctrine is that the less a person is seen or heard, the better the result. The body is clenched in odd positions, breathing slows. The minutest movements, which in turn trigger sounds and disturbances, are avoided. In the process of observing, the observer attempts to become invisible or rather to camouflage his presence. He is not involved. Actually, he isn’t there at all. The question I ask myself is how long can such a condition be maintained, and what happens when the pseudo-neutral observer suddenly becomes part of the recording.

In summer 2007, a friend of mine is arrested on the alleged charge of “terrorism”. Someone you know very well and whose stance you respect. The view of your surroundings change. The telephone sometimes crackles strangely, and the couple at the table beside yours was at the same restaurant as you a few days earlier.

“Day of the Sparrow” is an examination of the society in which I live. There are few traces of war – neither is it visible nor clearly located. The film tries to work out how and at what points do breaks open up the seemingly peaceful surface. Moments when war is visible, when the interfaces between civil life and military action blur. For me these points cannot be enumerated through a “realistic”, classic documentary way of working. It is about developing a filmic language which steers the focus to irregularities, which undermines familiar hierarchies of attention, which traces the small displacements in a seemingly homogenous image.

With “Day of the Sparrow”, I would like to create a filmic space between image and sound, analysis and imagination, which questions the apparent casualness of the current war.

Philip Scheffner, 10.01.2010

Of bird watchers and other incidental proceedings

Text by Nicole Wolf on DAY OF THE SPARROW, published in the catalogue of Berlinale Forum 2010

The day of the sparrow could be any day. Sparrows are in fact very close to us. They mostly stay where people are. But not every sparrow triggers the outraged and threatening reaction sparked by the one that on November 14, 2005, fell victim to the gambling and television spectacle of Domino Day in Leeuwarden, and henceforth becomes an affair of state. Day of the Sparrow begins with physical exertion. First the sparrow that slams into an obstructing windowpane, which it doesn’t perceive as such, then the carefree sparrows indulging in their daily baths in shallow water.

Day of the Sparrow is thus an animal film and, true to its genre, follows birds to their habitats, providing insight into their territoriality. It takes us to the meanders of the Mosel River, little villages and forests behind hilly fields in the Eifel region, flowery meadows, tranquil lakes in the woods, long sandy beaches and the open Baltic Sea, as well as to cities like Bonn, Berlin, and Leeuwarden. We often peer at length into multilayered wide open spaces and sometimes into the sky – but before the screen can turn into an abstract, idyllic landscape painting, a specific detail draws our attention or the film cuts to a precise close-up of a flock of birds or a Tornado fighter plane landing. The observer must often wait patiently in ambush and, following ornithological practice, pay as much attention to sounds close by as to distant ones; maybe also like the soldier lying in wait for the enemy - but that was another time. Gradually, an alongside, behind, in front, or in between develops. Ground that must not be tread, films never made, peripheral talk, questions and answers, about war, security, militarization, peace, participation, remaining silent, acting, and Afghanistan. Image and sound work together and against each other; concentration, friction; steadily and accumulatively our senses get confused. Without spectacular images or dramatic climaxes, the continuity of inconspicuous but precisely placed and constantly observing camera glimpses and of the sensitive build-up of a fragmentary but pointed net of thoughts and perspectives creates a tension and intensity that holds our breath, similar to the fixed attentive when a house of cards is set up. A cinematic surplus arises, the wonderful excess that we can experience when cinema is at its best; perhaps it can momentarily be circumscribed with thinking and seeing from the margins, a cinematic experiment in showing what cannot be enunciated.

The simultaneity of the death of a sparrow and of a German soldier in the Afghanistan war and continuous, seemingly coincidental overlaps, result in a well-conceived balancing act that never embraces unexpected parallels in interpretation, but unobtrusively and yet fundamentally questions our perception. Neither the potentialities disclosed by the occasionally silent long shots, nor the possibilities of being very close by ever pin down anything concrete. The insistence on silence, observation, persistent listening, and the offer to let our habitual perception run off the tracks lead to a cinematic openness that enables a shift in perspective. The relation between observer and observed blurs, also because the option of remaining external and uninvolved is denied, despite us looking from the distance. When the camera thus targets two soldiers of the Bundeswehr, Germany’s army, who slowly pace off their perimeter behind fences and, observing, consider whether these are intruders to be taken seriously; then this situation contains far more layers than gaze and reciprocal gaze could describe.

If the crisis of documentary film means that no new pictures can be made, that no really new stories can be told anymore, and that in the age of constant media confrontation with conflict zones we have lost our capacity for empathy because we have no relationship to the object of attention, then the Day of the Sparrow is a calm, insistent example of how documentary film, at any rate a particular documentary film, is precisely what can grow beyond the description of the world as we are able to see it today. If in the act of viewing the film produces the experience of a corporeal alienation effect in relation to familiar landscapes and confuses our embedding in certain pictorial, auditory and sensual contexts, then this carries the fascinating potential of the politics of aesthetics that might be the condition of political thought and action.

The use of the personal also receives a shift in the film; it is never employed as an entry, a legitimization, or a means of identification but nevertheless becomes part of Merle Kröger and Philip Scheffner’s carefully crafted script. Ways of questioning, political strategies, and chosen positions for the recording of images and sounds can be experienced as inhabited ones and hereby enable also the spectator to shift perspectives within and through the film. Perhaps she briefly feels like the gray heron, slowly moving across the street between the parking cars, self-confident in the stillness of the nocturnal city, but not for a second taking its watchful eye from the fundamental fragility of its surroundings.

In the end we are confronted with vital questions of taking action and how acting is tied to seeing, seeing to understanding, understanding to closeness, and closeness to involvement – or how we relate to what disturbs our peace seemingly only from afar.

Credits

Screenplay, Editor und Producer

Philip Scheffner, Merle Kröger

Director

Philip Scheffner

Director of Photography

Bernd Meiners, Philip Scheffner

Sound

Pascal Capitolin, Volker Zeigermann

Sound Design

Pascal Capitolin, Karsten Höfer, Philip Scheffner

Line Producer

Marcie Jost

Produced by

Pong Kröger Scheffner

In Cooperation with

Blinker Film, Meike Martens, Worklights Media Production, Marcie Jost und Peter Zorn, ZDF/ARTE (Doris Hepp)

Founded by

Medienboard Berlin Brandenburg, Mitteldeutsche Medienförderung, Filmstiftung NRW, Filmförderung Hamburg Schleswig-Holstein, Deutscher Filmförderfonds, FFA Drehbuchförderung, Werkleitz (Supported Artist)

World Premiere

Berlinale IFF (Forum) 2010

International Premiere

FID Marseille 2010 (International Competition)

DVD-Details

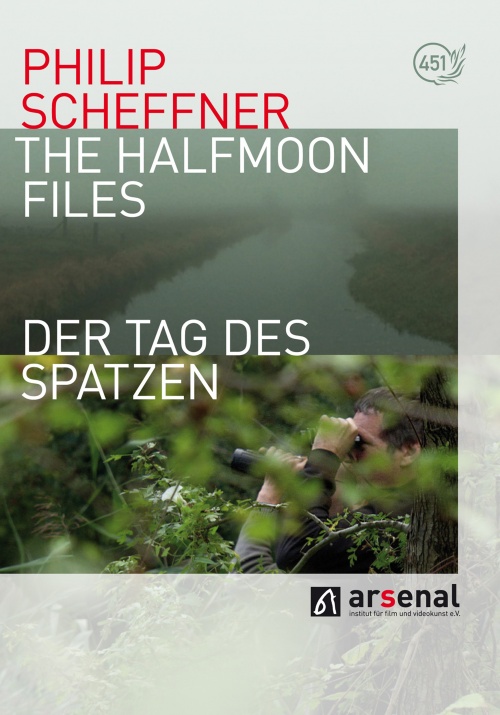

THE HALFMOON FILES and DAY OF THE SPARROW were released on one DVD in the Arsenal Edition.

Extras

20-page booklet

Language

THE HALFMOON FILES: German, English (partly original version with subtitles) | DAY OF THE SPARROW: German, English (partly original version with subtitles)

Subtitles

THE HALFMOON FILES: German, English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Turkish, Russian, Arabic, Hebrew, Japanese | DAY OF THE SPARROW: German, English, French

Country code

code-free

System

PAL Colour

Length

187 min | THE HALFMOON FILES (D 2007, 87 min) | DAY OF THE SPARROW (D 2010, 100 min)

Aspect ratio

16:9

Sound format

THE HALFMOON FILES: DD 2.0 | DAY OF THE SPARROW: DD 2.0 + 5.1

Rating

no age restriction