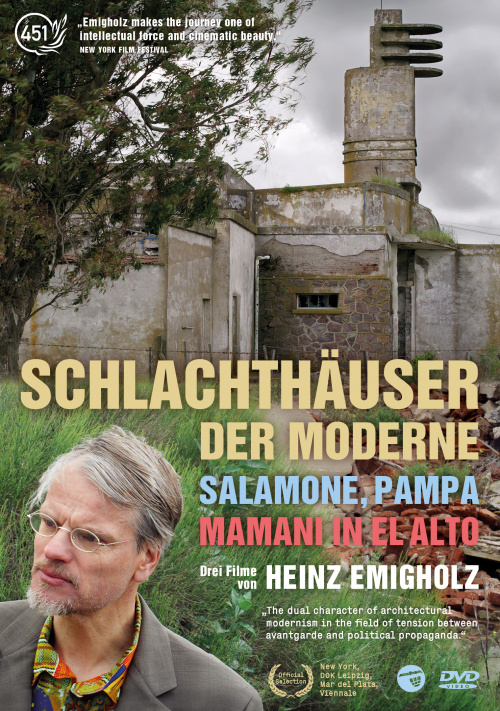

Schlachthäuser der Moderne

D 2022, 80 min

Die quasi-faschistische Architektur der Schlachthäuser Francisco Salamones in der argentinischen Pampa, die utopischen Bauwerke Freddy Mamani Silvestres in El Alto / Bolivien und das restaurative „Stadtschloss“ in Berlin sind die Eckpunkte eines analytischen Dokumentarfilms, der den Doppelcharakter der architektonischen Moderne im Spannungsfeld zwischen Avantgarde und politischer Propaganda untersucht. Der Schauspieler Stefan Kolosko agiert als Taucher in der versunkenen Stadt Epecuén und als Kurator im Berliner „Humboldt Forum“. Der Architekt Arno Brandlhuber kommentiert den Wiederaufbau des „Berliner Stadtschlosses“.

Die Dreharbeiten zum Film fanden 2021 in Berlin, Bolivien und Argentinien statt.

Synopsis

Die filmische Dokumentation der Bauwerke zweier südamerikanischer Architekten, die unterschiedlicher nicht sein könnten, bildet die Grundlage des Films SCHLACHTHÄUSER DER MODERNE, der den Doppelcharakter der architektonischen Moderne im ideologiegeladenen Spannungsfeld zwischen Avantgarde und politischer Propaganda untersucht. Der indigene bolivianische Architekt Freddy Mamani Silvestre (*1971) hat im kurzen Zeitraum von fünfzehn Jahren ab 2005 in der Stadt El Alto über sechzig Projekte verwirklicht, die abseits vom Stilkrampf und Diktat einer westlichen Moderne mit seiner eigenständigen Farb- und Formenwelt eine utopische Setzung bedeuten. Siebzig Jahre zuvor errichtete der argentinische Architekt Francisco Salamone (1897-1959) in der Provinz Buenos Aires innerhalb von zehn Jahren eine Vielzahl öffentlicher Gebäude, die vom Geist einer faschistisch-futuristischen Moderne durchdrungen sind. Der Gegensatz zwischen Experimentierkunst und strengem Politsymbolismus, zwischen verspieltem Engagement und öffentlichen Zwangsvorstellungen, kennzeichnen die Pole, die der Film im Kontext von Restauration und literarischer Verklärung analysiert. Das Projekt „Stadtschloss“ (aka „Humboldt Forum“) in Berlins Mitte dient mit seinem Versuch einer Synthese zwischen monströsem Prachtbau und reduktiver Moderne als dritter Eckpfeiler dieser Untersuchung. Die Tatsachen eines präfaschistischen Wilhelminismus und eine verschrobene südamerikanische Phantasie über den Kern des Nationalsozialismus sind das Bindeglied, die die in Europa relativ unbekannten Bauwerke von Salamone und Mamani mit dem Diskurs über den Doppelcharakter der Moderne, ihr Changieren zwischen Experiment und Restauration, verbindet.

Streaming-Info

Der Film ist über unseren Vimeo-Kanal zum Leihen oder Kaufen erhältlich.

Sprache: Deutsch, Untertitel: Englisch, Französisch, Spanisch, Deutsch (SDH)

Pressestimmen

Contemporary cinema’s preeminent chronicler of architecture and its intersection with the ever-present crisis of 20th-century modernity, Heinz Emigholz returns with an alternately mournful and sly treatise on how the presence—and, in some cases, absence—of municipal and communal building architecture is inseparable from capitalist ideology. Focusing mainly on cities and provinces in Argentina, Germany, and Bolivia, Emigholz’s latest film is a work of quiet observation and historical excavation. From slaughterhouses by Francisco Salamone to the flooded former spa city of Epecuén to the newly built Humboldt Forum in Berlin, the film demonstrates the effect of capital on public spaces, where creation and destruction go hand in hand, and as always, Emigholz makes the journey one of intellectual force and cinematic beauty. — New York Film Festival

Ein argentinischer Baumeister, der in der Pampa Rathäuser, Friedhofsportale und Schlachthäuser wie vom modernistischen Fließband gebaut hat. Dann ein bolivianischer Architekt, dessen grellbunte Zweckbauten im Hochland jeder Beschreibung und Vorstellung spotten. Schließlich mitten in Berlin ein neuer alter Palast. Zusammenhänge gibt es in Hülle und Fülle, erbaulich sind sie alle nicht. Heinz Emigholz nutzt sie für ein Pamphlet wider Stilvergessenheit und Geschichtsfälschung.

1983 erschien der erste Film in Heinz Emigholz’ Reihe „Photographie und jenseits“; mit den beiden Arbeiten, die DOK Leipzig in diesem Jahr in der Festivalsektion Camera Lucida zeigt, sind es bereits 35. Doch obwohl „Schlachthäuser der Moderne“ zahlreiche Sequenzen der anderen beiden Werke verwendet, hat er in Form und Duktus wenig mit ihnen gemein. Kommen die genannten, eher minimalistischen Filme ohne Kommentar und teils ohne Inserts aus, so zeichnet sich dieser durch seine kantigen Monologe und seinen Mut zum Stilbruch aus. Polemik und schwarzer Humor sind nichts Ungewöhnliches in Emigholz’ Universum. Doch so vergnügt auf Krawall gebürstet wie in dieser überaus facettenreichen Auseinandersetzung mit deutscher Geschichte und ihren hässlichen Ausprägungen hat man ihn bisher nicht erlebt. Kein Alterswerk, eher ein neuer Aufbruch. — Christoph Terhechte, DOK Leipzig

Making its world premiere in the CURRENTS section of the New York Film Festival this year is the newest structural treatise by acclaimed documentarian Heinz Emigholz: the brutally titled Slaughterhouses of Modernity. Intellectual and equally poetic, one need not carry a comprehensive understanding of modernism vis-à-vis postmodernism to be enraptured by Emigholz’s gift for montage. With canted camera angles and heroic close ups, Slaughterhouses of Modernity unfolds as a transfixing travelogue through the boundaries of nature and industry. Past and future. Civilization and apocalypse. Portraits of architecture that jut out like scars of a faded eon amidst indifferent topographies seeking to reclaim it. [...] Are these design practices inextricable from their cursed roots, or can they be reclaimed from their fascist mold? Emigholz has an answer, but the film isn’t just an 80-minute yes-or-no question. It’s a document of now, a history all its own. The film’s dynamic structural tableaus offer an unimpeded view of the present cast perpetually into the future. Like the structures photographed within it, Slaughterhouses of Modernity will also age out of the context it was made – to resist is to misunderstand the lessons of history. What will be left behind are breathtaking images of cinema’s most essential themes: that of time and space. – Anthony McKelroy, The Frida Cinema

Typically, in films past, Emigholz has relied almost exclusively on static shots of buildings, trusting in his raw footage and ambient soundtracks to do the speaking. The sheer size and scope of Slaughterhouses of Modernity (not to mention its vital message) demanded more, however. Emigholz has always referred to his films as “hard-core documentaries,” but the descriptor feels especially applicable to this cleverly cut, exhaustively researched, intelligently assembled crash course in the failings of 20th-century modernity. – Kayla McCulloch, Cinema St Louis

Libraries, court houses, churches, and (importantly for the film’s central thesis) slaughterhouses, mostly abandoned and in various states of decrepitude, reveal the retrospective ugliness — and broken promises — of this architectural ethos. The right angles and minimalist curves of now rust-streaked and flaking public buildings in the Buenos Aires Province towns of Pellegrini, Saldungaray, Laprida, Balcarce, Guaminí, Salliqueló, and Azul evoke a striving for aesthetic purity and strict functionalism that an architectural cognoscenti disillusioned with its aspirations (here represented by Emigholz) is eager to discredit. — Cosmo Bjorkenheim, Screen Slate

The titular slaughterhouses that “rise up like monuments or churches” in the pampas take the frame, each dominating the grassy plains around it. Some have been abandoned (one with an on-the-nose graffito: “Tell me baby, what’s your story?”), while others have been converted to museums or have at least been preserved. But the slaughterhouses merely serve as the central metaphor in Emigholz’s journey: afterwards, he shoots the flooded village of Villa Epecuén, the restoration of the Berlin Palace (which architect Arno Brandlhuber jumps in to editorialize as “one of the most disgusting buildings in the world”), and the antipode to these projects in Freddy Mamani Sylvestre’s utopian buildings of El Alto. — Zach Lewis, In Review Online

Dem Film selbst widerstrebt alle Klarheit und jedes Gleichmaß. Er greift in mehrere Richtungen gleichzeitig aus, ist in seinen Sprachpassagen – ein Faden übrigens, den Emigholz erst vor einigen Jahren wieder aufgenommen hat – zugleich witzig, wütend, resigniert und hoffnungsvoll. — Tilman Schumacher, critic.de

In nur 80 Minuten verpackt Emigholz eine solche Vielzahl an Ideen, Bildern und Referenzen und beweist dabei, dass ein Essayfilm zu keiner Sekunde langweilig sein muss. Unbedingt sehenswert! — Hans Bonhage, uncut.at

Ausgehend von der Doppeldeutigkeit des Filmtitels (kann laut Regisseur auch heißen: „Häuser, in denen die Moderne geschlachtet wird“) entwirft Heinz Emigholz in seinem neuen Essayfilm eine Argumentationskette, die von Schlachthäusern der 1930er Jahre in Argentinien (im bekannten Stil seiner Architekturfilme) bis zur (Teil)Wiedererrichtung des preußischen Stadtschlosses in Berlins Mitte (Emigholz: „Da wurde im wahrsten Sinne Mist gebaut“) reicht. Mittendrin: deutsche Nazis in Südamerika, die Kolonialpolitik des präfaschistischen deutschen Kaisers Wilhelm II. und die Kitschbauten eines bolivianischen Architekten in El Alto. Sarkastisch, wütend und sehr angriffslustig. — Lars Penning, Viennale

Emigholz jüngstes Werk SCHLACHTHÄUSER DER MODERNE nimmt diesen Gedanken nun in Form eines Essayfilms auf, der in Bolivien, Argentinien und Berlin entstand und Verbindungen und Einfluss zwischen europäischem und lateinamerikanischem Faschismus nachspürt, Kolonialverbrechen und Erinnerungskultur. Im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes Schlachthäuser entwarf der argentinische Architekt Francisco Salamone in der Provinz Buenos Aires in den 30er Jahren, längst verfallene Kathedralen der Moderne, die der expandierenden Produktion des weltweit gefragten argentinischen Rindfleisches dienten und an den Stil des italienischen Art Deco erinnern. Ganz anders das Barock des wiederaufgebauten Berliner Stadtschlosses, in dem einst der deutsche Kaiser den Genozid an den namibischen Völkern der Hereros und Namas in die Wege leitete, ein direkter Vorläufer und Inspiration des Holocaust. — Michael Meyns, Indiekino

It is a beautiful, quietly poetic and brilliantly complex film about our shared past, which is carefully pieced together by a director with a profound interest in those intricate details that accumulate to form the entire history of humanity, as seen through the buildings that were built long before we were born, and will likely stand for centuries after our demise, our lives just coinciding with the growing legacy these buildings and their architects have left behind in human history. (more) — Matthew Joseph Jenner, International Cinephile Society

Preise und Festivals

- New York Film Festival #60 im Lincoln Center

- DOK Leipzig - Deutscher Wettbewerb

- Viennale

- Mar del Plata IFF

- Cinema du Réel

- EMAF - European Media Art Festival

- JEONJU IFF

- IndieLisboa IFF

- Vilnius Documentary Film Festival

- FIFAAC - Compétition

Weitere Texte

Aus dem Prolog des Films

„Die revolutionären Erkenntnisse der theoretischen Physik zu Beginn des letzten Jahrhunderts führten zu einer unumkehrbaren Erschütterung traditioneller Raum-vorstellungen. Das hatte weitreichende Folgen für die Bereiche Architektur und Film. Die filmischen und architektonischen Avantgarden entsagten sich weitgehend der Tradition des Theaters mit seinen formelhaften Erzählweisen, barocken Ausstaffierungen und gestischem Gebaren. Zurück blieb ein Publikum, das in seinem persönlichen und politischen Erleben keinen Raum fand, diese Umwälzungen nachzuvollziehen und für sich selbst fruchtbar zu machen.

Religiöse und wirtschaftspolitische Zwangs- und Terrorsysteme verhinderten lange Zeit und immer wieder von Neuem einen aufgeklärten Umgang mit wissen-schaftlichen Erkenntnissen. Deren Einzug in einen neu zu definierenden mensch-lichen Gestaltungsrahmen blieb auf der Strecke. In dieser nicht überschaubaren, geschweige denn zu regelnden Situation begannen Begriffe wie Tradition, Moderne oder Postmoderne ein von gesellschaftlichen Realitäten relativ abgelöstes Eigen-leben zu führen. Sie seilten sich in den Bereich politischer Propaganda, ge-schmackspolizeilicher Anstrengungen und individueller Verwirklichungsmythen ab.

Angesichts des scheinbar unvermeidlichen Aufstiegs und des gleichzeitig logischen Niedergangs eines westlich geprägten Imperialismus und dem späteren Zerfall der politischen Blöcke nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg wurde die Verwirrung intellektueller Gemüter immer aufdringlicher. Voreilig wurde ein Ende der Geschichte deklamiert, und alles schien wieder möglich zu sein: Die Proklamation einer Situation, die für die Kunst ein erstrebenswerter Zustand sein mag, politisch aber nur die nächste Autokratie bis hin zum nächsten Terror ansagt…“

Heinz Emigholz im Interview mit Christian Flemm vom Filmmaker Magazine 2022

Filmmaker: Slaughterhouses of Modernity opens on the streets of El Alto, Bolivia, to piles of stones and views of doghouses, before ceding to images of dogs rifling through rubbish.

Emigholz: The filmmaker in Streetscapes [Dialogue] says to his analyst: “I can film a Le Corbusier building, but I could film a dogshed instead, and it would be a nice film, too.” I always had the desire to do just that. There are “Gehry”- and “Hadid”-kennels, doghouses in all possible modern styles.

Filmmaker: If a house, represented as two parallel, vertical lines with a unifying horizontal placed overtop, may be seen as the starting point for any conception of interior and exterior space, everything that follows might well be mere ornamentation. We’re well within the territory of architectural functionalism.

Emigholz: Don’t forget the cave, no right angles there. To build a safe place against the cold and the heat, against the rain and snow, is not at all trivial. But your statement reminds me of a joke by Adolf Loos: “When we find a mound in the forest, six foot long and three foot wide, with the shovels formed into a pyramid, we become serious and an inner voice tells us, someone is buried here. That is architecture.”

Filmmaker: In the hands of another filmmaker — Wim Wenders, for instance — this could have been an elegy to Modernism and its regimes of representation. But as John Erdman’s sardonic voiceover recapitulates a critical history of the 20th century, it is clear you have an ax to grind.

Emigholz: Slaughterhouses of Modernity is building up an argument, very slowly, discursively; through architecture and dog houses; through the “New Man” that the various ideologies wanted to build in the last century, and the aesthetic regimes that came with them; through the aftermath of the First World War, which lay the grounds for the Nazis; the activities of the Bauhaus; by paraphrasing a text of Jorge Luis Borges, and so on. It makes a point, right from the beginning, that something turned out to be deeply wrong.

Filmmaker: Erdman’s narration locates the origins of Modernism at the outset of the 20th century, in the “revolutionary findings of theoretical physics,” which led artists, writers and philosophers to “distance themselves from traditional beliefs about space.” I wonder if you could offer a personal, clarifying definition of Modernism that is beyond the works of art and literature that are often prescribed that label.

Emigholz: I am referring to existing definitions of Modernism, but I have no inclination to define it myself. I think there is no real substrate there anymore. “E=mc2,” of course, is one.

Filmmaker: Your inquiry is directed towards the European-inflected Modernism that made its way into South American architecture via colonial activities. You take us to Argentina, to see the slaughterhouses of Francisco Salamone and to Bolivia, to the festival halls designed by the indigenous architect Freddy Mamani Silvestre. A significant portion of the film also takes place in Berlin, where you live. What brought you back?

Emigholz: The film is ultimately about the Stadtschloss in Berlin and Wilhelm II, the last German Kaiser. He was an ur-Nazi. I am still personally attached to him, because he killed my grandfathers. The European aristocratic regimes got rid of the social movements by killing off their proletarians. My grandfathers were both carpenters in their twenties. Their wives were poor and left alone with children to take care of, both families were destroyed. So, the set was prepared for the appearance of a “strong Führer.”

Filmmaker: Then why spend a large part of the film in Argentina around abandoned slaughterhouses?

Emigholz: The problems I am dealing with are universal, a global network of destruction. The architect of the slaughterhouses, Francisco Salamone, was greatly influenced by fascist architects in Italy. As the film turns to his cemetery portal and slaughterhouse designs, slowly we begin to travel down the drain of Modernism. At the time of their construction, Argentina was incredibly rich: during the war they sold meat to all belligerent parties. That the slaughterhouses were built as monumental symbols is just nuts. The province of Buenos Aires had so much money that Salamone could realize his fantasies as a surplus. The slaughterhouses were eventually abandoned because of economic forces, the need to centralize the business. Few people outside Argentina know about them. I like to do research work with film.

Das vollständige Interview könnt ihr beim Filmmaker Magazine lesen.

Credits

Buch und Regie

Heinz Emigholz

Mit

Stefan Kolosko, Arno Brandlhuber

Stimmen

Susanne Bredehöft, Heinz Emigholz, Kiev Stingl

Kamera

Heinz Emigholz, Till Beckmann

Assistenz

Manja Ebert

Set Design

Ueli Etter

Originalton

Esteban Bellotto, Rainer Gerlach, Ueli Etter, Markus Ruff

Schnitt

Till Beckmann, Heinz Emigholz

Recherche

Angelika Hinterbrandner, Olaf Schäfer

Lokales Management Argentinien

Esteban Bellotto

Lokales Management Bolivien

Angel Cordero, Konrad Schlaich

Tongestaltung und Mischung

Christian Obermaier, Jochen Jezussek

Musik

Kiev Stingl „Einsam WEISS boys“

Postproduktion

Till Beckmann

Produktionsleitung

Viviana Kammel, Günter Thimm (rbb)

Produktionsassistenz

Anna Bitter

Redaktion

Rolf Bergmann (rbb)

Produzenten

Frieder Schlaich, Irene von Alberti

Produktion

Filmgalerie 451

Koproduktion

Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg

Gefördert durch

Die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien und Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg

Uraufführung

09.10.2022, New York Film Festival

Kinostart (DE)

19.01.2023

Ausschnitt aus dem Film „P.R.“ von Mathieu Brohan

Ausschnitt aus dem Film „Miscellanea II“ von Heinz Emigholz

Dank an Arno Brandlhuber, Mathieu Brohan, Viviana Castro, Eugenia Cavallaro, Victor Choque, Angel Cordero, Marcelo Guardia Crespo, Hartmut Dorgerloh, Rubén Ghio, Alfred Hagemann, Ulrike Lorenz, Alejo Magarinos, Vanesa Neubauer, Camila Paredes, Jonathan Perel, Sergio Picazo, Ana Ramos, Freddy Mamani Silvestre, María Sueldo, Maia Vena, Hanns Zischler und Centro Cultural Salamone in Balcarce, Chamber of Commerce in Guamini, Offices of Culture in Alem, Azul, Carhué, Laprida, Pringles, Saliqueló und Pellegrini, Office of Tourism in Tres Lomas und Pym Films

DVD-Infos

Extras

Disc 1: Interview mit dem bolivianischen Architekten Freddy Mamani

Disc 2: MAMANI IN EL ALTO (Heinz Emigholz, D 2022, ca. 95 min), SALAMONE, PAMPA (Heinz Emigholz, D 2022, ca. 62 min), Booklet mit einem Text von Heinz Emigholz zu den drei Filmen (Deutsch / Englisch)

Sprache

Deutsch, Englisch

Untertitel

Deutsch, Englisch, Französisch

Regionalcode

0

System

PAL, Farbe

Laufzeit

237 min

Bildformat

16:9

Tonformat

Dolby Digital 2.0 + 5.1

Inhalt

Softbox (Set Inhalt: 2)

Veröffentlichung

27.10.2023

FSK

12

Kinoverleih-Infos

Verleihkopien

DCP (2K, Farbe, 5.1, 25 fps)

Bildformat

16:9

Sprache

Englische Fassung

Deutsche Fassung (optional englische Untertitel)

Werbematerial

A1-Poster

Lizenzgebiet

Weltweit

FSK

Ab 12 Jahren